|

Anton Batagov piano cycle

A landmark work that changed the coordinate system of contemporary music (Vedomosti newspaper).

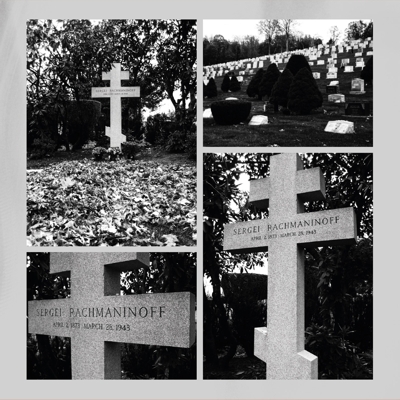

1 At the Grave of Sergei Rachmaninoff (Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, NY)

© 2013 Fancymusic, 2018 Melodia

In October 2012 I visited Rachmaninoff's grave. He is buried at Kensico Cemetery in the hamlet of Valhalla, half an hour’s ride from New York City. The cemetery is surrounded by picturesque mountains, well-tended houses, manicured lawns, and idyllic lakes and streams. Rachmaninoff is buried among actors, writers, politicians, military personnel, and business people, together with "ordinary mortals" from all over the world – Americans, Russians, Estonians, Chinese people... A great musician who heard the universe as a powerful, boundless space resounding with the sounds of bells at once both tragic and triumphant, Rachmaninoff left Russia and became a part of a completely different world… As I stood at his grave, I found this space resonating within me. When I returned home, I began writing a piano cycle. In this cycle, Rachmaninoff writes letters to postmodern composers. Rachmaninoff himself was an anti-modernist. He was not a revolutionary, was never "ahead of his time," and was unafraid of looking old-fashioned. At first glance, it would seem that he bore no influence on late 20th/early 21st century composers. Nonetheless, his invisible, magical presence can in fact be heard in the music of some composers, including so-called "contemporary classical" composers and rock musicians. Likewise, when I hear Rachmaninoff's endless melodies that evolve from a very short motive of literally two or three notes, the word "minimalism" all but rolls off my tongue… However, these connections are so subtle and not readily apparent that I wouldn't want to deaden them by invoking musicological terms. Rachmaninoff thus speaks to the composers that would come after him. Among composers of his time, he did not find a receptive audience – unsurprising, perhaps, given the avant-garde experiments consuming the musical world at the time. The generation that followed Rachmaninoff essentially continued along the avant-garde path. However, Rachmaninoff looked even further ahead, taking sight of those with whom he desired to speak heart-to-heart. We have long been accustomed to the fact that both early music and classical music are used as the building materials for new compositions. Time runs quickly, and we are already at the next turn of the spiral. Music written only a short while ago becomes itself material for today’s meditation. In this process, there are no quotations; there are only stylistic journeys in a time machine. The turns of this spiral resonate with one another, and we listen to the sounds they make. Translation by William Quillen and AB

|