CD 1 Ouverture Jesus bleibet meine Freude (Jesus, Joy of Man’s Desiring) Total time: 65.24 CD 2

Recorded at Constructor Hall, ZiL cultural centre, Moscow, December 2016 Thanks to: Oxana Levko (Yamaha Artist Services Moscow), (c) Melodia 2017 ______________

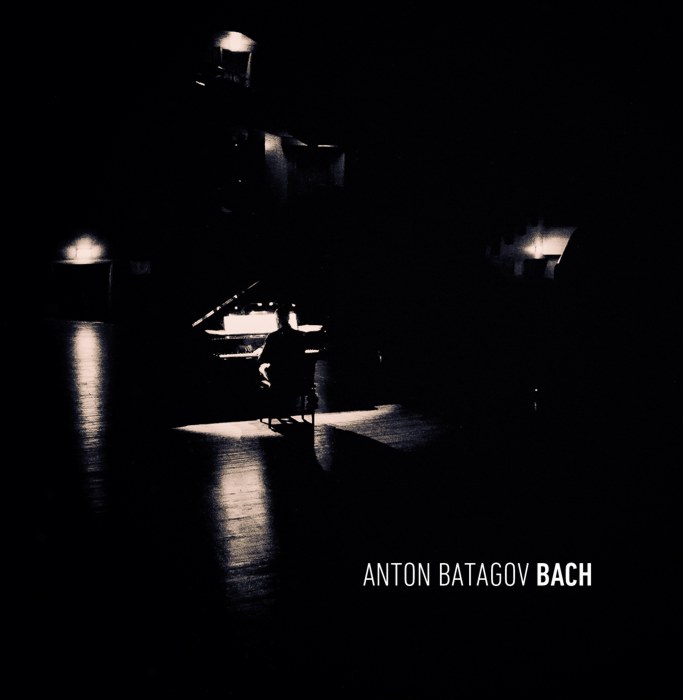

I am looking at the score bearing the name of Bach. I don't know how Bach would like it to be played. I doubt we 21st century musicians can claim we know how to play Bach in an authentic manner. An attempt to recreate a playing style, which we never heard, by studying musicological texts is just a pleasant self-deception. That’s why I don’t seek historical authenticity. I want to stay where I am – here and now – and try to actually hear the sounds, which have lost their meaning in the endless stream of consumption. You may argue that Glenn Gould did this long ago. Yes, indeed. But Gould died in 1982, and the world has changed quite a lot since then. Thanks to the minimalism, we discovered the magic of timeless meditative states. Post-modernist approach dramatically changed our understanding of the author's role. Modern culture is an intellectual game played by new rules. It is a puzzle that consists of quotations and stylistic mirrors. Over the last decades, we have successfully learned these rules and memorized the names of the pioneers. When we hear something that reminds us of early music, we know that this is Michael Nyman. Music with swinging minor thirds and wavelike passages is Philip Glass. A reminiscence of medieval polyphony is Arvo P ä rt. As for performing classical music, it is a factory that is still functioning. We come on stage wearing tuxedos and reproduce the sequences of notes written by someone who lived in the 19th century and in the early 20th century over and over again, mimicking "classical" and "romantic" emotions. What does this phenomenon have to do with modern life? Nothing at all. Can we now breathe the 19th century air? No. We live in the era of air conditioning. The world as a whole has become a continuous process of consumption. Music has become background noise. You can hear it everywhere, but nobody notices, even when it is loud. These vibrations equal silence to the modern person’s ear. Forty years ago, people sat down at home and listened to a record. Today's people are so busy with thousands of extremely important things that they cannot afford to spend a whole hour listening to music. While listening to music, you can answer dozens of emails and messages, chat with people from all over the world via various messengers, have lunch, shop online, watch the news and the weather forecast, check stock market indexes, book plane tickets… And do all of the above without leaving Facebook for a second. Or, if listening to music in a car, we can cover at least 35 miles during this hour... We have completely lost our ability to concentrate on anything. If Bach could see all this, and then watched a modern TV commercial or a music video, he would think he was in hell. Gould would think he was in a mental asylum. That's why I'd like to play Bach now in such a way that these sounds don't pass by like anything we hear today. Each section of his music should be repeated twice, and I play them in different tempos with different articulation, as if contemplating a crystal from different points of view, or living a life twice choosing different scenarios. The tempos are mostly slow, but it's not about the tempos per se. Every sound appears spontaneously, as though it was an improvisation, and reveals another meaning, another kind of expressiveness. It's like zooming in on a picture to see every detail in high resolution. This meditative concentration has its inner non-linear flow of time. Time is a relative thing. It is not necessary to be Einstein or an astronaut going to the final frontier to see that this is true. You don't have to be a Buddhist monk to realize that all our concepts are relative and empty. Anyway, it's clear that Bach's music contains all of our post-modernism, all of our minimalism, as well as jazz, rock, and many other styles. A curious fact: the music of Partitas has almost nothing to do with "dance" names of their movements. Bach chose the form commonly used at the time – a dance suite – and filled it with completely different content. The E minor Partita is like a Passion without words, and the D major Partita is a mystery of Christmas. Between these two partitas, I will play a choral Jesus bleibet meine Freude ( Jesus , Joy of Man's Desiring) from cantata Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben (Heart and Mouth and Deed and Life). It will be the centerpiece of this two-hour program, and there is no need to explain what it is all about. Every note, every intonation, every chord in Bach's music convey the truth that makes everything else insignificant. That's why it sounds so uncompromising, sometimes even ruthless, while being so dazzlingly beautiful. There is no path to light that would not go through Calvary. I don't know whether I will be able to convey at least a tiny part of this truth of Bach's. I doubt it. But I will try. _______________________ Every time I choose а piano for my recordings I want the instrument to comply with the challenge I face in terms of sound, and it’s always a different challenge. My albums of the recent years were recorded on 1932 and 1959 Steinways, and a Fazioli. However, I decided to record this program on the Bösendorfer that I had “accidentally” found at the Yamaha Artist Services showroom. Bösendorfer is a true aristocrat in the world of pianos. It has a very special sound, noble and deep, detailed and kind of multilayered. Yamaha has owned the old Austrian brand Bösendorfer since 2008. So I called Oksana Levko, the artistic director of Yamaha Artist Services Moscow, and asked her if I could make this recording on that piano. She said, “You can. It has just been moved to ZiL cultural centre, and there it stands in a small hall and is taken good care of.” So it was arranged that the recording would be done with that grand piano in that hall. And now I get to the main point. The place where ZiL cultural centre was built in the 1930’s had earlier been the necropolis of the Simonov Monastery. The monastery was established in the 14th century by St. Feodor, a disciple of Venerable Sergius of Radonezh. During the Soviet era, the monastery was destroyed (just a very small part of it remained in place) as well as the cemetery where poet Venevitinov, writer Aksakov, composer Alabiev, art collector Bakhrushin, a Pushkin’s uncle, and numerous members of Russian noble families had been buried. The communists killed not only the living, but the dead too, with the destroyed sacred objects acting as the best kind of foundation for the proletarian culture. I had been aware of the history of that monastery and ZiL cultural centre, but when I came there and started to play… At first it seemed to me I would simply be unable to play there at all. You can either keep silent or pray there. But then I felt that Bach’s music was the kind of silence/prayer that was possibly appropriate in that situation, and even essential in a way. I had never had a recording as difficult as this one. Every note seemed to absorb all that, and it seemed that the events of the past are taking place right now. Definitely, if I was recording it, for example, at the Grand Hall of the Conservatory (we were considering that option at some point), or if this very piano was someplace else, I would have played differently. But of course it was destined to happen at that very place. And one more story related to this recording. Every time I work in a recording or mixing studio, I thank my teacher Severin Vasilievich Pazukhin, an outstanding audio engineer. Thanks to him, I became not only a musician, but also an audio engineer, too. I’m always very demanding when it comes to sound, therefore it’s important to discuss everything and be on the same page with an audio engineer to find the right approach together. Words like “XLR connector,” “compressor threshold” or “cardioid microphone” are as much my mother tongue as “F natural,” “allegro” or “crescendo.” The choice of microphones is of primary importance for recording. Recording engineer Anastasia Lukina asked me, “How should it sound?” I tried to find some words, but I couldn’t. Then she suggested, “Let me bring a few pairs of different mics, you’ll play this piano, we’ll listen, compare and choose.” That was the right idea indeed. And there we are, with a forest of microphones – Neumann, Schoeps, Sennheiser, DPA. We had a possibility to choose from the world’s best models with optimal parameters for piano recording. And Nastya says, “There’s a man coming with Russian Elation mics. I saw them in Los Angeles. I think they sound great. Let’s try them too.” So I’m sitting and playing, Nastya is recording. Then she calls me to the control room to listen. I’m listening. Nastya is switching the tracks for me to compare how the same thing recorded with different pair of mics sounds. And suddenly... “Wow, what’s this? This is exactly what I need!” “That’s Elation.” I didn’t give it a second thought. We chose Elation. I’m not going to badmouth the rest of the world famous mics; they are fine. But these ones are fundamentally different. An absolutely natural sound, warm and breathing – “analogue” if you please. These mics sound as if it wasn’t a recording at all. They sound as if you were just sitting and listening to a live performance. It’s unusual to see the inscription Made in Russia on a device like that. Don’t you agree? Anton Batagov

|

LISTEN / BUY